Research

Topics My Lab Has Been Studying

Intimacy, Closeness, and Responsiveness

What makes a relationship feel close? And what can partners do to strengthen their sense of connection in a relationship? In the late 1980s, we developed the Intimacy Process Model, which has since sparked decades of innovative research on these and related questions. The model proposes that intimacy begins when one partner chooses to be open, sharing personally meaningful aspects of their beliefs, feelings, or experiences. It deepens when the other partner is responsive—that is, listens attentively, with curiosity, support, and warmth. A sense of intimacy emerges when person who shares experiences their partner’s response as:

- understanding—the sense that the listener truly grasps what was said and “gets the fact right”;

- validating—the feeling that your perspective is valued and appreciated (even if not fully shared);

- caring—the perception that the listener is genuinely concerned for your well-being.

Over the years, we and other researchers have used this model to understand many aspects of relationships—from satisfaction and closeness to longevity and breakups, and even the spark of interpersonal chemistry. A recent Annual Review of Psychology article described this model of responsiveness as one of the “14 core principles” of close relationships.

Capitalizing on Good Fortune

One day, Shelly Gable and I noticed a striking pattern in the relationships literature: most studies focused on problems—how couples deal with conflict, cope with stress, or manage declines in satisfaction. This focus seemed lopsided. After all, who begins a relationship with the goal of confronting difficulties? Rather, we bond because relationships are enjoyable and rewarding. This observation led us to begin studying a process called “capitalization”—the act of amplifying the joy of a positive event (whether acing a test, getting a job promotion, or finding a twenty-dollar bill on the street) by sharing the news with someone else. For example, we’ve shown that relating happy news to a close friend amplifies happiness over and above the event itself.

Our studies have shown that the listener’s response matters greatly—capitalization works only when the response is authentically engaged and enthusiastic. For example, our research finds that enthusiastic responses lead speakers to evaluate their stories more positively, strengthen their sense of liking, trust, and gratitude toward the listener, and feel in a better mood. In contrast, ambivalent responses—those that seem halfhearted or disinterested—leave speakers uncertain of how their news is being received, while openly critical or dismissing responses tend to be even more damaging. Interestingly enough, these descriptions may apply primarily to Western contexts. In one study, we’ve shown that muted and even critical responses do not seem to have the same negative consequences in Asian couples.

People Benefit from Responsiveness …

The benefits of responsiveness aren’t limited to relationships—they influence how we think, behave, and feel as individuals. There’s a simple explanation here: we are social beings, evolved with a fundamental “need to belong”—that is, a need to form stable, positive, and meaningful connections with others. Our research shows that when our associates are perceived to be responsive—when they demonstrate understanding, validation, and genuine concern for our well-being—feelings of loneliness diminish. Responsiveness also fosters what scholars call “intellectual humility”—a willingness to be open-minded, to be less egocentrically biased, to recognize that one’s own perspective may not be the only valid one, and to acknowledge differing points of view without defensiveness. Perceived responsiveness can even reduce prejudice toward outgroups.

… and from Good Listening

A question I often get is, “How can I be a responsive listener?” Although there is no simple checklist of behaviors that guarantee success, research conducted by my collaborator Guy Itzchakov (University of Haifa) offers valuable guidance. Guy, one of the world’s leading experts on listening, has shown that high-quality listening involves three main components: attentiveness, comprehension, and positive intention. When these qualities are conveyed—both through words and nonverbal expressions—people feel genuinely heard and understood. This, in turn, allows them to reap the many relational and personal benefits that responsiveness provides. Our research shows that listening with genuine curiosity is the surest way to help a speaker feel well responded to. Looking ahead, I anticipate important theoretical and empirical advances that integrate our understanding of responsiveness and listening.

Our Partners Can Help Us Regulate Our Emotions

One of the most natural things we do after an emotional experience is turn to other people. We reach out for support and advice, for sympathy or distraction, to share good news, or simply to be heard by a compassionate ear. Given how common this is, it’s striking that the vast majority of research on emotion regulation focuses only on what people do by themselves. Our work takes a different approach: we look at coping with emotions through the lens of relationships. How can partners help us manage our emotions? What kind of relationships are most effective in helping us deal with our feelings? How can people learn to be effective helping their friends and partners handle their emotions?

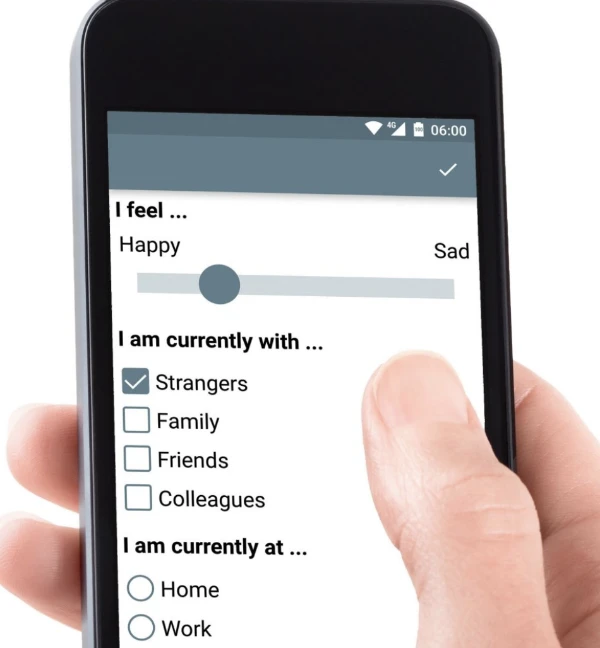

Studying Relationships in Their Natural Environment: Everyday Experience Methods

In our research, we use many tools—experiments, surveys, archival methods—but we are especially interested in methods that capture everyday experience life in its natural context. Our two favorite methods are called experience sampling and daily diaries. These approaches let us examine people’s thoughts, feelings, and activities as they occur in, or close to, real time, rather than relying on memories, general impressions, or contrived settings. For example, in some studies, we signal people at random moments throughout their day, asking them to record what they were doing, thinking, and feeling at that moment. In other studies, we check in with participants at the end of each day for several weeks, giving us a chance to understand the natural ups and downs of everyday life. Our lab was among the first to use these methods and we continue to innovate with new ways to apply them—providing fresh insights into how relationships shape everyday experience.