Research Interests

- Mechanisms of aging

- Comparative biology of aging

- DNA repair and genomic instability

- Anticancer therapy

Our research focus is on understanding the mechanisms of longevity and cancer resistance. Aging is the major cause of death in developed countries. By finding ways to delay aging it will be possible to delay the onset of multiple age-related diseases. Cancer is another major killer in developed world, where 25% of human mortality is caused by cancer. Cancer incidence increases exponentially with age and to achieve long-life species must evolve efficient tumor suppressor mechanisms. Our goal is to understand such mechanisms in mammalian species that are naturally cancer-resistant.

Comparative Biology of Aging

Animal species differ dramatically in their aging rates and susceptibility to age-related diseases. Comparative studies on animals with different maximum lifespans (MLS) can be used to identify the molecular mechanisms that explain this disparity. Studying rodents (phylogenetically related with a 10-fold difference in MLS), bats (exceptional longevity compared to body size), and the bowhead whale (MLS > 200 years) allows us to identify such health- and lifespan-extending mechanisms. This knowledge enables the development of interventions to prevent, delay, or cure age-related diseases in humans.

Genomic Stability & Epigenetics of Aging

Sirt6

We and others have found that Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) extends mammalian lifespan and promotes healthspan. It does so by maintaining genomic stability through improved efficiency of DNA repair, maintenance of heterochromatin and suppression of transposable elements. We are currently working on regulating SIRT6 as a potential strategy for rejuvenation.

LINE1

We and collaborators have shown that LINE1s, selfish genetic elements found abundantly in humans, promote age-associated inflammation in cells. We are currently working on silencing LINE1s via genetic or pharmacological approaches will alleviate age-related pathologies.

Tumor suppressor mechanisms in long-lived rodents

Cancer affects most, if not all, classes of vertebrates. The major tumor suppressor pathway appear to be conserved among mammalian species, however, the cancer rates are strikingly different. For example, up to 95% of mice die from cancer, whereas another rodent, the naked mole rat appears to be cancer proof. Human cancer mortality is 25%, which is in somewhat in-between the mouse and the naked mole-rat. In addition to its cancer resistance naked mole-rat is highly interesting due to its longevity. It has the maximum lifespan of 30 years, which is almost 10 times longer than a similar size mouse. We recently discovered that the naked mole-rat has a novel anticancer mechanism named “early contact inhibition” that contribute to its cancer resistance. We are interested in the genes and signaling pathways involved in early contact inhibition and in other mechanisms that contribute to naked mole-rat longevity and cancer resistance. Eastern grey squirrel is another very interesting rodent. Grey squirrels are common in cities and parks across the United States, but a few people know that these rodents have a maximum lifespan of 24 years. Squirrels express extremely high telomerase activity in all tissues, comparable to human tumor tissue. High telomerase activity is generally associated with increased cancer risk; therefore squirrels must possess unique mechanisms that allow them to stay cancer free despite the high telomerase activity.

Sirtuins – Mammalian Sirt proteins in regulation of stress response during aging

Yeast Sir2 gene is a histone deacetylase involved in gene silencing. Furthermore overexpression of Sir2 extends yeast lifespan and promotes genome stability. Mammals have seven homologs of Sir2 named sirtuins (SIRT1-SIRT7). Deletion of mouse SIRT6 leads to premature aging and genomic instability. We are interested in the role of SIRT6 in genome stability and stress resistance.

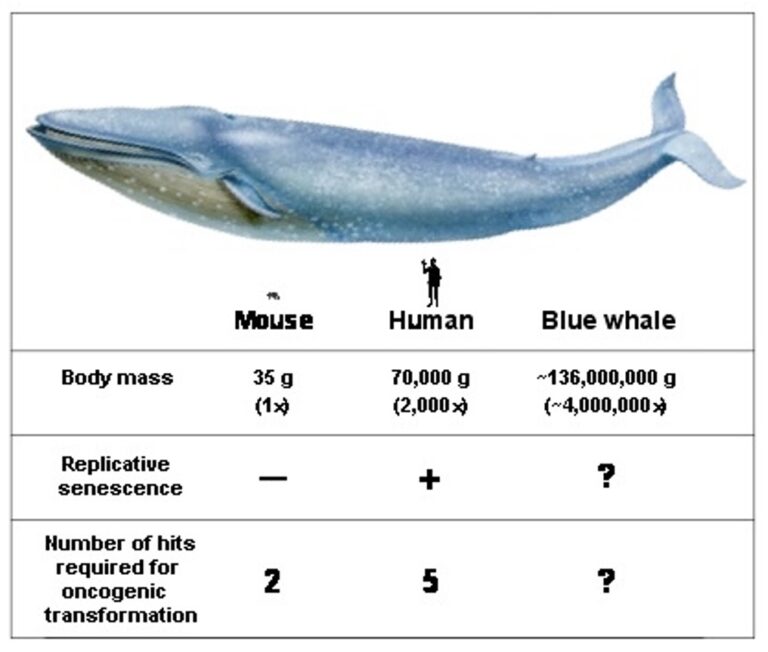

Anticancer mechanisms in whales

If all mammals were equally susceptible to oncogenic mutations and had equal tumor suppressor mechanisms one would expect that the rate of cancer would be proportional to the species body size and longevity. This is because greater number of cells and greater number of cell divisions would increase the chances of malignant transformation. Mammals range in body size from 30 g mouse to 110,000,000 g blue whale. If up to 95% of mice die of cancer by the age of 2 years it is paradoxical how come blue whales do not succumb to cancer in the womb. This fundamental question is named “Peto’s paradox” after Sir Richard Peto, who described it in 1975. The most plausible solution to Peto’s paradox is that the large and long-lived species have evolved superior anticancer systems. We are interested in understanding these mechanisms with the goal of using them to prevent human cancer.

Enumeration of anticancer mechanisms in mouse, human, and blue whale

These three species differ in body mass by a factor of 2,000: human is 2,000 times larger than a mouse, and blue whale is 2,000 times larger than a human. Humans have multiple additional anticancer adaptations compared to mice. It is currently unknown whether whales have evolved many additional anticancer adaptations compared to humans. Body mass in large whales is difficult to measure. Therefore, the figures are approximate estimates.