Department News

Matson Group ‘cleaves’ oxygen from surface of metal oxide, enhancing reactivity

Metal oxides have been shown to be effective catalysts in converting greenhouse gases to useful chemical fuels, for example transforming carbon dioxide into methanol.

However, the development of new solid-state catalysts for these types of chemical transformations is “very much driven by ‘guess and check,’” says Ellen Matson, assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Rochester. “A critical challenge is understanding the atomic-level interactions between these gaseous environmental pollutants and the catalytically active sites on the metallic oxides.”

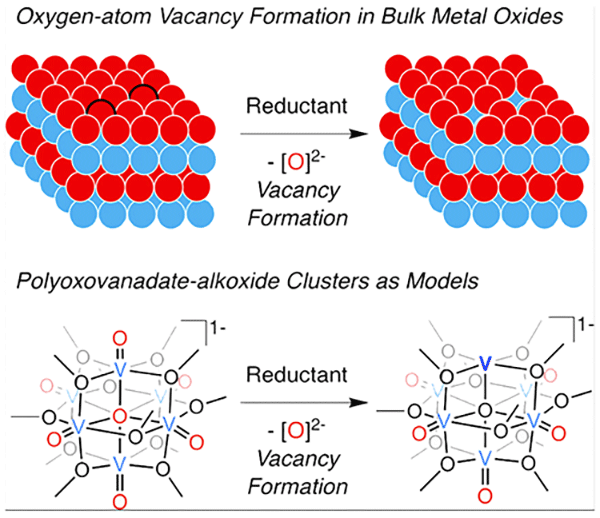

Now her lab has found a way to model these interactions experimentally, hopefully leading to the elimination of much of the guesswork in designing more effective catalysts for the production of chemical fuels. In a paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, lead author Brittney Petel, a PhD student in Matson’s lab, describes creating – for the first time – an oxygen-atom vacancy at the surface of a metallic oxide cluster, in this case a polyoxovanadate cluster containing vanadium. This exciting discovery proves that molecular assemblies can function as pieces of larger assemblies, serving as structural models for bulk metal oxide materials.

The vacancy, created by the removal or “cleavage” of an oxygen atom, makes it easier for the gaseous mixture to reach and bind with a redox-active vanadium cation, or positively charged ion.

“Theoretical investigations in recent years have suggested that creation of an oxygen-atom vacancy at the surface of metal oxide materials is often a key step in facilitating a reaction,” Matson says. “By extending this chemistry to polyoxometalates (a class of metal oxide clusters than can also include molybdenum or tungsten), we have demonstrated that our clusters can model the surface chemistry of extended solids. This idea has been tossed around for decades by chemists, and for the first time our lab is realizing these types of goals in cluster research!”

“What’s cool about modeling the surface chemistry with a discrete molecule like this is that we can monitor these types of complicated, multi-electron reactions spectroscopically. We can take CO2 or another oxygenated substrate, add it to a reaction vessel that contains our reduced polyoxovanadate cluster, and watch, in real-time, how the two compounds react.”

“What we are hoping,” she adds, “is that our findings can influence the way materials chemists design their systems – how they pick the materials they’re going to put into their solid-state reactors to see if they produce the reactions they’re looking for. This is a new and exciting approach for testing some of the scientific hypotheses that have been promoted through theory. Understanding the surface chemistry through experiments will really change the scope of understanding of the reactivity of materials.”

Serendipitous solutions

The discovery came about “almost serendipitously,” Matson says. The lab used a reducing agent to cleave an element-oxygen bond “in work with our iron-functionalized polyoxovanadate clusters.” When a gaseous substrate, like nitric oxide, is bound to iron in these clusters, exposure of the system to a reductant results in loss of an oxygen atom.

“We were super excited at first, thinking that we had cleaved the N=O bond of the substrate,” Matson says. “However, our results were pretty confusing, and we set aside the data for awhile.” Later, in thoughtful control experiments involving all-vanadium versions of the cluster, Petel used the same reducing agent, and confirmed the loss of oxygen atoms at the surface through mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Other research teams across the country are also exploring the synthesis and reactivity of multimetallic clusters, in particular their reactivity with small molecules. However, most research groups have focused on modelling the active sites of metalloenzymes, mimicking chemistry performed in nature, Matson says.

“What makes our program so distinct is that we’re studying these multi-metallic assemblies as models of extended solids, for materials applications. We’re carving out a new area where we’re digging into some really exciting mechanisms for small molecule activation. It’s an incredibly exciting direction for our research group!”

Polyoxovanadate clusters have provided a fruitful area of research for the Matson Laboratory. In 2017, Matson received a National Science Foundation CAREER award study the formation of heterometallic polyoxovanadate clusters. The overarching goal of this research is to generate catalysts capable of storing multiple electrons, that more efficiently convert greenhouse gases to useful chemical fuels. The Matson Laboratory continues to push boundaries with these hexavanadate cluster, earlier this year reporting the modification of polyoxovanadate-alkoxide clusters for more efficient electrochemical energy storage in a redox flow battery.

William Brennessel, an X-ray crystallographer and scientist with the Department of Chemistry, also contributed to the research for this paper.